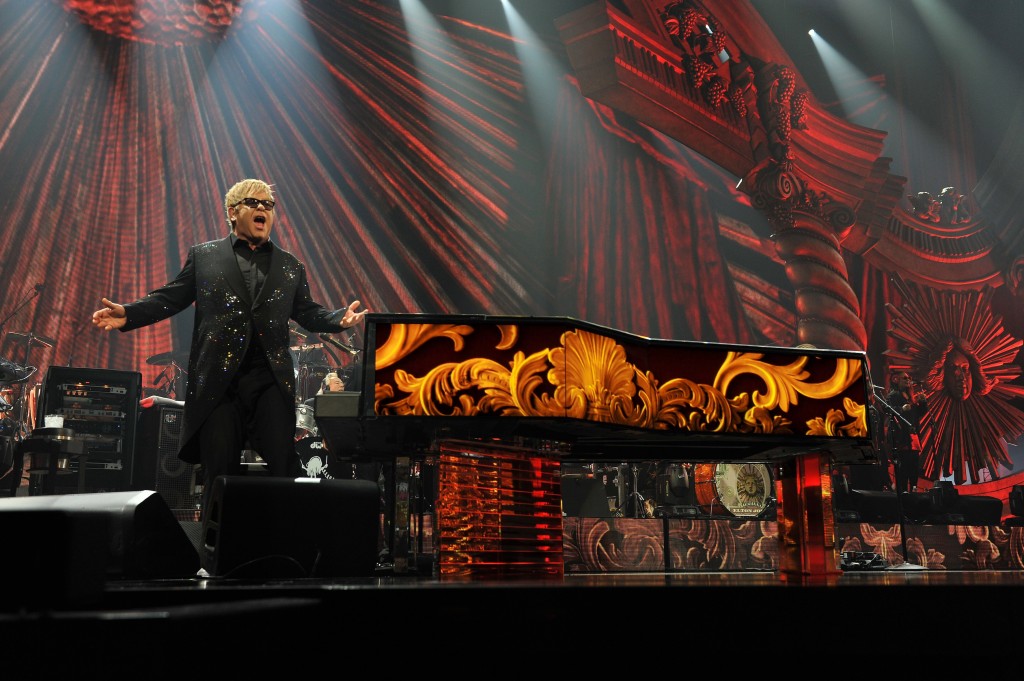

There are few spectacles as grand as a performance by Sir Elton John. And at The Colosseum at Caesar’s Palace in fabulous Las Vegas, live performances simply don’t get much better. Sadly, this residency show isn’t practical for many people to see, and though the Rocket Man is scheduled to touch down in Middle Tennessee as a Bonnaroo headliner this summer, the outdoor mega-festival may not provide the same magic of seeing an artist of Elton’s caliber. So, Yamaha Entertainment Group of America had the foresight to bring the music legend to the silver screen in The Million Dollar Piano, which hits theaters state-side March 18th and 26th, including showings at the Regal Cinemas at Opry Mills and Green Hills.

We had the opportunity to speak with Chris Gero, founder and Vice President of Yamaha Entertainment Group who also served as the producer and director of the cinematic concert that serves as a crown jewel in a showcase of music regality. You can check out our interview below, and check into tickets for local showings right here.

No Country: In terms of wearing the director’s hat, what inspired your efforts with this project?

Gero: Well, I wanted it to be as close as possible to sitting in a seat. Obviously, through your career, you look at a lot of material, you look through a lot of footage and films from other folks. You take from some things that you really dig, and sort of discard the stuff that you don’t. The show itself is so grand and epic, and it is really the first time that Elton had brought in some high-end designers and light directors on a show like this. I wanted it to represent what you saw live, if you were there in the theater. It is such a huge production, and the staging is so gorgeous and lush and overwhelming. We wanted to make certain that we represented that to the greatest degree. It was really trying to capture that without setting Elton upside down. Meaning having cameras in his face, and cameras all over the place. That would be counter-productive to him.

No Country: So your goal was to capture the art without getting in the way of the artist? That must have been quite a feat, especially when you’re working around one of the biggest artists in music.

Gero: Correct. When you’re doing a show… and you know, Elton and I have worked together for many years. But when you’re doing something like this, when you’re producing a live event, you’re kind of in control from beginning to end with everything that happens. This is very different. You’re directing a film shoot to a live event, and it’s kind of like two armies converging to form this ballet. And both armies do separate things. You’ve got this show going on, which has to run perfectly. Then you’ve got this kind of mini-show going on in the background to make sure that everything is captured perfectly. As you know, Elton is one of the biggest artists on the planet, and as he’s gotten older, he’s really used to not being tugged at. We wanted to make it as simple as possible for him not to feel the pressure of all of these cameras floating around and distract him in any way. That’s a really big challenge.

No Country: It’s refreshing to think that even someone as big as Elton John can still be distracted by the camera.

Gero: Oh, it’s totally true. He doesn’t like to see the machinery, so to speak. He doesn’t like to see the mechanics of things. He loves technology, and he would sooner ask you about your camera… “Oh, what does it do?”. But when he gets up onstage, he wants to make sure that he connects with his audience. That’s where he gets his adrenaline from. You just can’t have forty cameras in his face, you know, and flying robotic cameras and steady-cams and all these different mechanics. It’s a pretty big ballet that went on during the filming process.

No Country: Is that what the viewers should expect from this? A ballet of visuals?

Gero: What it is, it’s a remarkable representation of his body of work. It’s two hours of just hit after hit after hit, and then there’s a few moments that not very many people have ever seen. There’s a breakout segment of two or three songs where it’s just Elton and Ray Cooper. They did a very famous tour through Russia as he was the first pop artist to tour in the late seventies. So there’s really kind of a throwback moment to that. But all the imagery and lighting is absolutely world-class. It’s just this truly phenomenal experience. It’s very dynamic, very moving. It’s a lot more fluid than previous concert footage of him. He allowed us a lot closer access this time.

No Country: So, you’ve had the pleasure of collaborating with Sir Elton on past work? How did that partnership originate?

Gero: For lack of better terminology, Elton came to Yamaha out of frustration with a previous relationship he had had with another piano manufacturer. Somebody had suggested that he try Yamaha, and the relationship just kind of languished for a couple of years. Then I was brought in to establish a much-more reciprocal relationship. I started a dialogue with him directly; immediately. We became friends, and on the musical product side, we’ve been partners for nearly 22 years. And things kind of grew from there. Everything we do as far as branding, 99% of it is done through our talent. And he’s the biggest star we have in our roster.

So it grew from there, and we started branching out on the projects that we worked on. We would help with maybe the AIDS Foundation, or we would help with some little film that represented him in some way, etc. The very first large-format show that I produced with him was in 2003, 11 years ago. Then I was brought in to consult on the first Vegas show, which was Red Piano. I’ve enjoyed a more significant role with this second Vegas show. Over a long course of time it just became this very trusting, family atmosphere.

No Country: You mentioned having looked over older content for this show. Are there any particular live shows that you went to as an artistic inspiration?

Gero: To be honest, what I did was I went back and starting looking at… When Elton made the decision to bring in some of these really world-class guys. One of them being a gentleman by the name of Mark Fisher, who is now deceased but was a very famous stage designer. Another guy being Patrick Woodroffe, and another being Tony King. All of these guys were wickedly, wickedly high-end. Elton had never done anything like this before. Previously, he had collaborated with David LaChapelle who started as a very well-known photographer, and went into videography and pop-art. Red Piano was a lot David LaChapelle’s influence, as he came in as a creative director on that show. That’s where I started. Although I’ve seen over a thousand different films over my career on artists, I wanted to get a sense of what was good and what was not good about that. But then I started looking at all of the stuff that was related to these other guys that were being brought in. The U2 stuff, and the Martin Scorsese film on the Rolling Stones, and a lot of the Cirque de Soleil stuff. Because we were shooting two elements. We were shooting the documentary and the live concert as well. The goal was to marry the two together so that they were inter-threaded. Those were the influences in which I counted on. I knew we couldn’t shoot a really great art-house thing because we didn’t have the time and the access to be able to do that. We’ve spent four years essentially filming this from beginning to end, but we couldn’t follow Elton from point A to point B all around the world because everything was based in Las Vegas. So we focused instead on the making of the piano which was completely unique by itself, and we focused the film work on making the live concert.

No Country: Stupid question, but I feel compelled to ask: Is the piano actually worth a million dollars?

Gero: It’s actually cost $1.4 million to make. It’s kind of funny. We started, with really just Elton and his Tour Director Keith Bradley, but we started at the last year of Red Piano an “off-the-cuff” dialogue on what it would look like if they were to do a new show. The run of Red Piano was just ending, and they were gonna do a couple years of a hiatus, but none of that was under contract or agreed upon. But they came to me and started coming up with ideas of a piano for the next one. When I was a kid, listening to Elton, I lived in an era where nothing was imagined for you. You had to do it for yourself. And every song was a great story in my head. There were all these motion pictures in my head. What I wanted that to be translated through was the piano. And it’s very interesting how Elton describes the piano as this black, monolith plank that just sits there, static on the stage.

I heard him say that to somebody one time, I just happened to be standing in the room. And I thought to myself “Well what if it wasn’t anymore”? So I thought to myself, it would be really great if we made an instrument that if you turned if off, if would look just like a piano. But if it were turned on, it would be part of the set, or it could disappear into the set, or it could be the center. And it could compel equally the story of what’s being told onstage as a living character with Elton. It’s a living, tactile piece of the show and it completes the show, becoming part of the story with him. So I went back, and sat down with him and his manager and from there sprung the design competition within the design team in Yamaha in Hamamatsu, Japan and a design was chosen. And Elton is one of the greatest art collectors of our time. He’s just so brilliant. He has this appreciation for the arts, and we wanted to make sure this piano was a piece of art. Like nothing else existed on the planet. The design that was picked was done by a twenty-six year-old female designer out of the lab, Akie Hinokio. Her idea was that no matter where you were in the room, it would reflect light. The piano’s was made of a very thick acrylic, and the complete inner workings of the piano are sixty-eight LED screens, all state-of-the-art. Three millimeter LEDs. There’s a higher resolution out now, but this is high definition. It was so high definition that when we put it on the stage for the very first time at Caesar’s Palace, it was like the sun and everything else was the just the stars around it. It was so bright and powerful. We actually had to tint the piano down even further by reducing the brightness. It was a little hairy there at the end, but it all worked out. The piano took about two years to build, and it was a four year process from beginning to end. It was a feat of engineering, first by Yamaha and then the company that did the LED screens which is a company called LSI Saco Technologies in Montreal. So the mockup started in my office, and the idea went from me to Japan, and then to Elton. In the entire process, Elton never asked a question about it until he saw the piano on stage. We’d have a conversation, and I’d start to say something, and he’d say “Don’t tell me, I don’t wanna know”. That’s how he was with the whole show. He just trusted you.

So what had happened was that the million dollar piano existed before the Million Dollar Piano show. And that’s where everyone had to take their cues. It was exciting to see this idea come to life that just came from this casual conversation.

No Country: You are currently working on another documentary project titled 88. Could we get you to go into detail about it?

Gero: Sure. With 88, I like to do a lot of stuff that’s philanthropic and meaningful, and kind of has a bit of a history marker to it. I’ve worked with a lot of stars. I was really close to Ray Charles, and had the pleasure of producing him on a couple of occasions. Some of these guys had kind of got away; having passed away before I had really had an opportunity to capture how they played piano. And before George Gershwin passed away, somebody had the foresight to have him record, to a player piano, a huge volume of his work. And we took that technology now in the digital age and turned that from the analog punch-outs of a player piano into a digital playback. So if you look up those files now, you can actually get the playback of how he intended to play these compositions. And there’s a technology that we own: the Yamaha Disklavier. It’s a type of fancy digital playback system with fiber optics and patented technology. So I wanted to tell a story of these guys, before they pass away or get any older. I wanted to tell a story about who their influences are, and how they play their music. To put it in perspective, we have a lot of these songs where you can literally see every note that’s being played back on the piano. It’s the audio and video. You see exactly any kind of mistakes that were made, or the entire intention. So imagine if we had that for someone like Beethoven or Mozart. We have the tableture, but we don’t really know what the exact intention was because you’re not really seeing in three dimension the exact intent of how he played it. Here you see absolutely everything. So I kind of went on a journey with going to artists, asking them “Who are you influenced by, what was the song that influenced you, and what was the significance”? We started last year filming all of these artists, and it’s just been a growing project. The reason it’s called 88 is because there’s 88 artists, and we’ re just starting. But what’s funny is that as we’re going, we’ve found is that a lot of these artists are influenced by each other, so they’re playing their own songs. You get on guy playing a Stevie Wonder song, and you get another guy playing a Stevie Wonder song, and another guy who is playing somebody else’s song. It’s a beautiful circle of artists that are explaining why the piano is important in our history, and what influenced them to become a piano player. What they’re literally doing is playing this composition that inspired them, and the end result is to have both the film and really a kind of presentation. For example, something you would see at a museum. There’d be a piano, like the Yamaha Disklavier, and there would be screens where you could pick an artist, such as Ingrid Michaelson. She might talk about how her parents were really influential in her music, and how she had one particular song she would play over and over again, and she would be playing it, but there would be actual playback happening at the same time from the piano. It’s all been recorded at the same time. From there, we picked five artists that best represented, including Elton, talking about the piano’s role in modern society.

The genesis of the entire project started with an article that was in the New York Times that was entitled something to the effect of “The Big, Black, Dead Elephant in Your Living Room”. It explained the death of the piano, and how it’s just a piece of furniture. I was pretty incensed by that. So this was really kind of my answer to that. It was never supposed to be a “Save the Piano” kind of thing. This is just how I feel. So I started just reaching out to artists’ friends and saying “Jump in”. It’s not a for-profit film in any way. It’s my own personal challenge.

No Country: So, to clarify, this journalist was saying that the cultural importance of the piano to current music is dead?

Gero: Yeah, maybe it was just kind of shock journalism. I’m not really sure. But the piano is really kind of the gateway instrument in this day and age. And you would absolutely be stunned by the amount of artists, and celebrities, no matter what they play everyone gravitates to the piano. I was a little shocked by reading it. You can’t be more wrong. It just became my own little message to the world.

To check out Million Dollar Piano, be sure to visit CinemaLive’s website. You can also purchase tickets to the screenings via Fandango for showtimes at the Green Hills or Opry Mills Regal Cinemas in Nashville.

![[NO COUNTRY PREMIERE] Touma Feels Haunted by the Ghost of Loss in New Single and Video, “Overture”](https://nocountry.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/uploads/2023/08/Touma-2023-2-1800-Credit-Carly-Butler-350x250.jpg)

![[NO COUNTRY PREMIERE] Touma Explores Growth and Deconstruction with Captivating, Earnest New Single and Video, “Lost, Found”](https://nocountry.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/uploads/2023/04/Touma-2023-1800-Credit-Carly-Butler-350x250.jpg)

![[PREMIERE] Notelle Gets into the Halloween Spirit with Spooky Lyric Video for “Ex-Lover”](https://nocountry.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/uploads/2022/10/Notelle-1800-350x250.jpg)